Great Expectations, Fragile Foundations

Lessons about growth from the CHLOE & BOnES reports

Was this forwarded to you by a friend? Sign up, and get your own copy of the news that matters sent to your inbox every week. Sign up for the On EdTech newsletter. Interested in additional analysis? Try with our 30-day free trial and Upgrade to the On EdTech+ newsletter.

I’ve been tracking a rising trend in online learning that many of you have seen up close: institutional leaders - presidents, provosts, CFOs, etc - setting growth ambitions that soar far beyond what’s operationally or organizationally possible. I’ve spoken with online learning leaders handed targets like “$75 million in online revenue within 10 years,” “from 0 to 65 online programs in five years,” or “7% growth next semester.” These aren’t so much strategic goals as they are budgetary lifelines thrown from the top floor.

The problem? These ambitions are often detached from reality, untethered from the state of faculty readiness, infrastructure, staffing, policy maturity, or market viability. And while anecdotes about this gap are easy to find, hard data on its prevalence has been elusive.

That’s where the CHLOE 10 survey (Quality Matters/Eduventures Research/EDUCAUSE) and the UPCEA Benchmarking Online Enterprises (BOnES) report come in. They offer a rare, data-driven view into how Chief Online Learning Officers (COLOs) are navigating this tension between expectations and capabilities. The data they offer show just how strained institutions already are, even when pursuing what appear to be far more modest growth goals than what I hear about.

Growth projections in CHLOE

The CHLOE report describe a world in which interest in online learning is growing fast. It further describes institutional projections for growth.

* 17% of Public 4Y institutions plan to add 10 or more fully online programs in the next three years (compared with 3% of Private 4Y and 9% of Public 2Y). This sector shows both the strongest projected program growth overall and the broadest distribution across growth categories, reflecting a more varied set of strategies.

* Private 4Y institutions lean toward modest to medium growth (59% small growth; 27% medium growth).

* Public 2Y institutions are most likely to anticipate modest expansion (49% expect small growth; 18% medium growth). It’s also notable that 25% of community colleges expect no program growth, suggesting a potential plateau in that sector.

These may seem like modest goals, but looking only at the number of new programs can mask much of the underlying growth ambition. As the pro forma for a new undergraduate program shows, the plan is for enrollment to double within five years. In other words, even if the number of programs is growing slowly, the aspirations for student enrollment growth may be more aggressive.

I’ve reviewed hundreds of these pro formas over the past few months, and these kinds of aspirations are typical.

Still, the expectations reflected in CHLOE aren’t the language of gold-rush optimism, they’re the measured realism of people who see the inside of the machine.

Increasing strains despite investment

The BOnES report shows that online learning budgets are increasing.

The average 2025 online enterprise budget was $8.1 million dollars, while the median was $4.5 million. The average gross revenue was $23.8 million, while the median was $11 million. Between 2024 and 2025, the average budget decreased by roughly $450,000, yet the median increased by $1 million. On the surface, these data points are seemingly at odds with each appear contradictory. However, the 2024 average was inflated by one supremely large online enterprise. For gross revenue, the average revenue for online enterprises increased by roughly $5.8 million dollars to $23.8 million, while the median increased by roughly $4.3 million to $11 million. Collectively, these figures illustrate that online enterprises are receiving increased attention and resources from leadership and finding improved efficiencies, which is yielding increased gross revenues.

Even with relatively modest aspirations, the CHLOE report shows how institutional systems are increasingly stretched.

Faculty readiness is a major bottleneck. Only 28% of faculty are fully prepared to design online courses, and just 45% are fully prepared to teach them.

Support structures are shaky. Adjuncts shoulder a disproportionate share of online teaching but often lack the support and integration needed to be part of core planning. At large institutions, contingent faculty handle 47% of all online instruction.

Decentralization hinders scalability. Many institutions have expanded online through a “department-led” approach, a recipe for inconsistency and missed opportunities to leverage economies of scale in technology, marketing, and course design.

Cultural resistance remains strong. Many COLOs say faculty and deans still believe in-person learning is “just better,” creating headwinds even for modest online growth. As one respondent at a four-year institution with a large online presence put it:

Supportive departments [that] see the value in online may have very different levels of responsiveness compared to academic departments [that] are begrudgingly online. There is definitely a growing belief that students “should” be on-ground and are only choosing online because it’s easy/ convenient. Never mind the very real and growing population of nontraditional learners who can only take online classes, and the very real and growing population of traditional-aged learners who prefer online classes; many faculty/deans take a paternalistic, “we know what’s best” approach.

The less tangible strains

What’s missing from the reports, but comes up frequently in conversations with clients and online learning leaders—are the less tangible strains and gaps in online learning organizational maturity. Two stand out in particular:

Lack of communication between leadership and operations. Often there are neither shared beliefs, understandings or goals across an institution or even within a particular chain of command. Neither does information about the nature of the online market and capabilities within the organization flow freely among units or up and down within the organization.

One consultant shared with me a case where the university president had ambitious online growth goals, but the provost didn’t share them, and no one had translated those goals into concrete actions for deans or department chairs.

Policy and infrastructure backlogs. Ambitions for online learning growth often race ahead while critical policies around academic integrity, intellectual property, and course quality remain underdeveloped, stalling progress at precisely the moments when clarity is most needed. We do get a hint of this policy gap in the CHLOE survey in widespread unhappiness among COLO’s around internal revenue sharing arrangements and the often crazy patchwork of arrangements that institutions have in place.

Even on the financial side, the mismatch is glaring. Despite significant investment in online learning, most of it directed toward additional personnel according to the BOnES survey, growth expectations are rarely accompanied by corresponding increases in marketing budgets. This gap becomes especially problematic when new programs are launched or when rapid enrollment growth is demanded, even though marketing is one of the clearest levers for driving that growth. As one COLO said to me about their previous institution.

they were always quick to ask us to increase enrollment within the next semester, but they never came with the additional marketing dollars to make that possible

A better way?

There’s no universal blueprint for online growth, as the CHLOE and BOnES surveys make clear. Success depends on an institution’s mission, available resources, leadership alignment, and capacity to partner where needed. While there may be no single right answer, there are plenty of wrong ones.

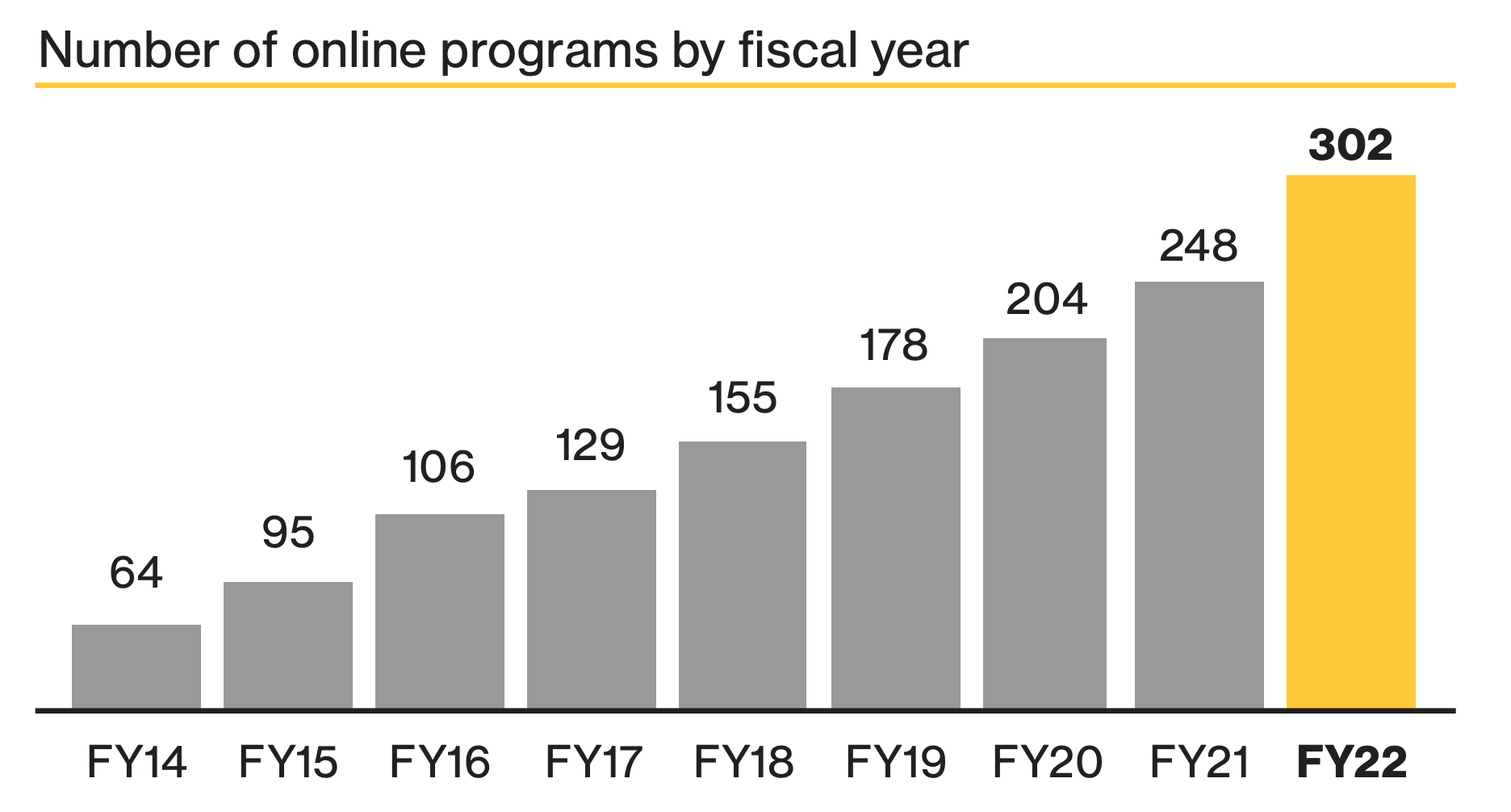

Arizona State University, often cited as the archetype of online scale, is a case in point as seen in this annual report with its dramatic growth in programs and enrollments.

It’s an institution well worthy of admiration, and there’s much to learn from them (I, for one, regularly pester one of their senior leaders with questions, which she graciously answers). But ASU is not necessarily the best general model for other institutions seeking online growth, and here’s why:

Different market conditions. ASU’s growth began in an earlier period, when the market was less saturated and conditions were more favorable.

High-growth OPM partnership. For its first decade, ASU worked with a high-growth OPM, a model that can accelerate growth but is neither advisable or feasible for every institution.

Visionary leadership. The institution benefited from a strong, visionary leader willing to make the bold moves needed to achieve rapid scale.

These conditions simply aren’t replicable for most institutions.

A more realistic model might be found in Oregon State University, the University of Central Florida, or the creation of University of Florida Online - examples of steady, strategic growth grounded in building internal capacity.

From OSU:

And UF Online:

Parting thoughts

Ultimately, what we need is not just more ambition but better ambition. Ambition rooted in a realistic understanding of institutional capacity, a shared strategic vision, investments in policy and infrastructure, and a culture that supports online learning as a core part of the academic mission, not an auxiliary one. It’s time we talked about what it really takes to grow online learning , and where ambition needs to be matched by structure.

The main On EdTech newsletter is free to share in part or in whole. All we ask is attribution.

Thanks for being a subscriber.