Many Explanations are Making Premature Analysis on Recent Grad Unemployment

We need to understand and address the more immediate causes

Was this forwarded to you by a friend? Sign up, and get your own copy of the news that matters sent to your inbox every week. Sign up for the On EdTech newsletter. Interested in additional analysis? Upgrade to the On EdTech+ newsletter.

A while back, I wrote a response to a widely discussed study by Brynjolfsson, Chandar, and Chen on the impact of AI on recent college graduates. The study concluded that some occupations are more affected by AI than others and that, in those fields, employment for new graduates has taken a hit.

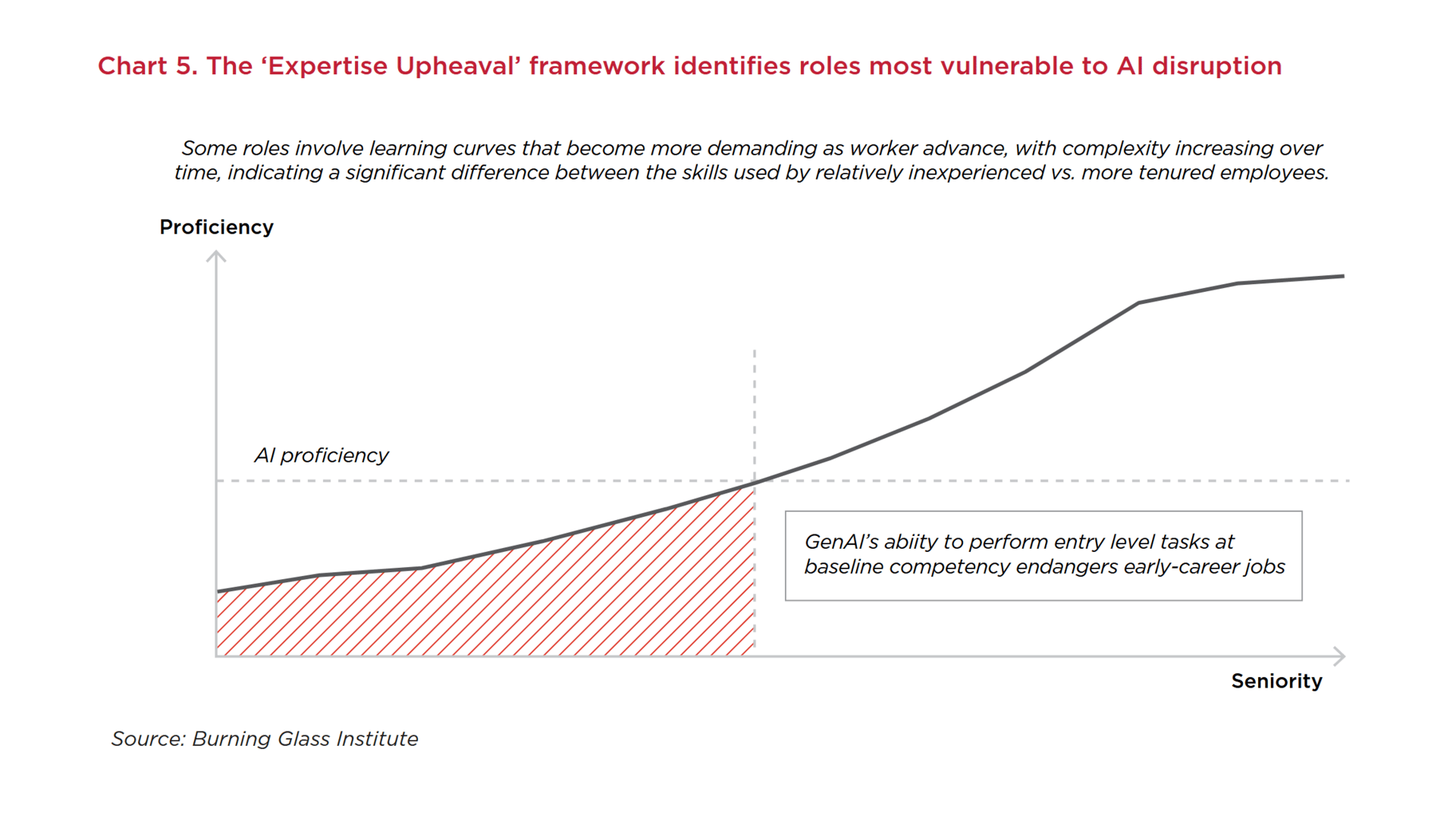

Since then, numerous observers have expanded on and amplified this issue, most notably the Burning Glass Institute in its report No Country for Young Grads. The report argues that the job market has undergone a structural change driven by the impact of AI. The authors posit a fundamental shift in how proficiency and experience on the job are developed, what they term an “expertise upheaval.” AI is now capable of doing much of the grunt work through which new employees used to learn the ropes and build the skills that propelled them into more senior roles. As a result, there are increasingly fewer opportunities for new graduates. The job market is becoming more top heavy, more of an inverted pyramid than the bottom-heavy structure it used to be.

The Burning Glass account is compelling. Hiring of new graduates is undeniably way down, and we see growing evidence of companies using AI to automate less skilled tasks.

But the argument is also, if not wrong, at least premature. Among other issues, the falloff in new graduate hiring predates the widespread adoption of generative AI. Despite these problems, it is an account that has gained a lot of traction. Because of this, there is a real danger that efforts to address the issue will be focused on the wrong thing.

In this post, I make the following arguments:

New graduates are facing an unprecedentedly difficult job market.

In the medium to longer term, Burning Glass is probably (though not certainly) right that there will be a structural change in how expertise is created.

This has not happened yet. If we in higher education focus primarily on the structural shift, we will likely miss the more immediate causes of the hiring slump. This will have serious implications for current and future graduates, who will struggle in the job market.

Instead, we need a two-stage solution. First, we need to address the proximal causes of weak graduate hiring. Then we can focus our attention on ways to respond to the shift in expertise. The two solutions are likely related, but they are not the same.

The recent graduate hiring trough

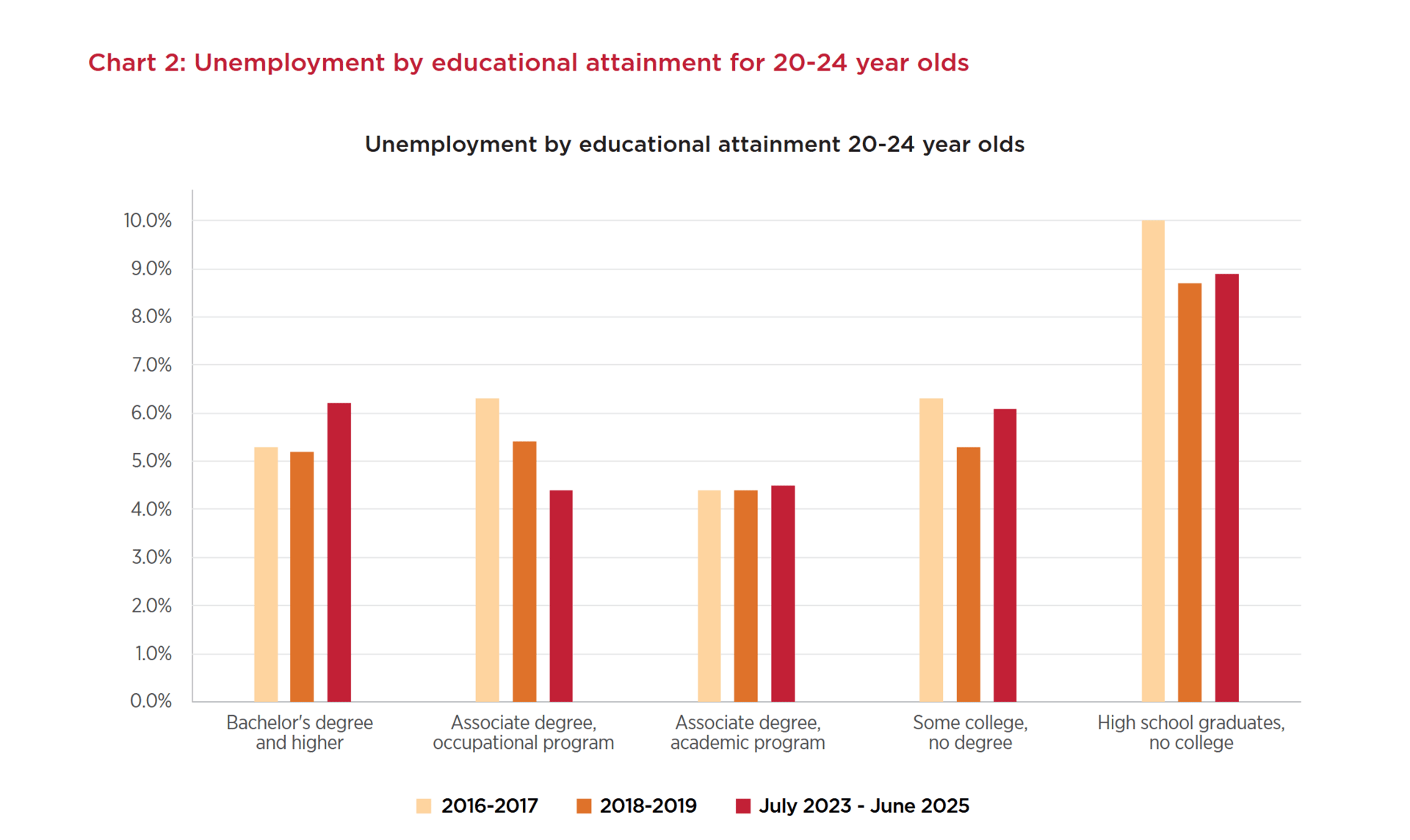

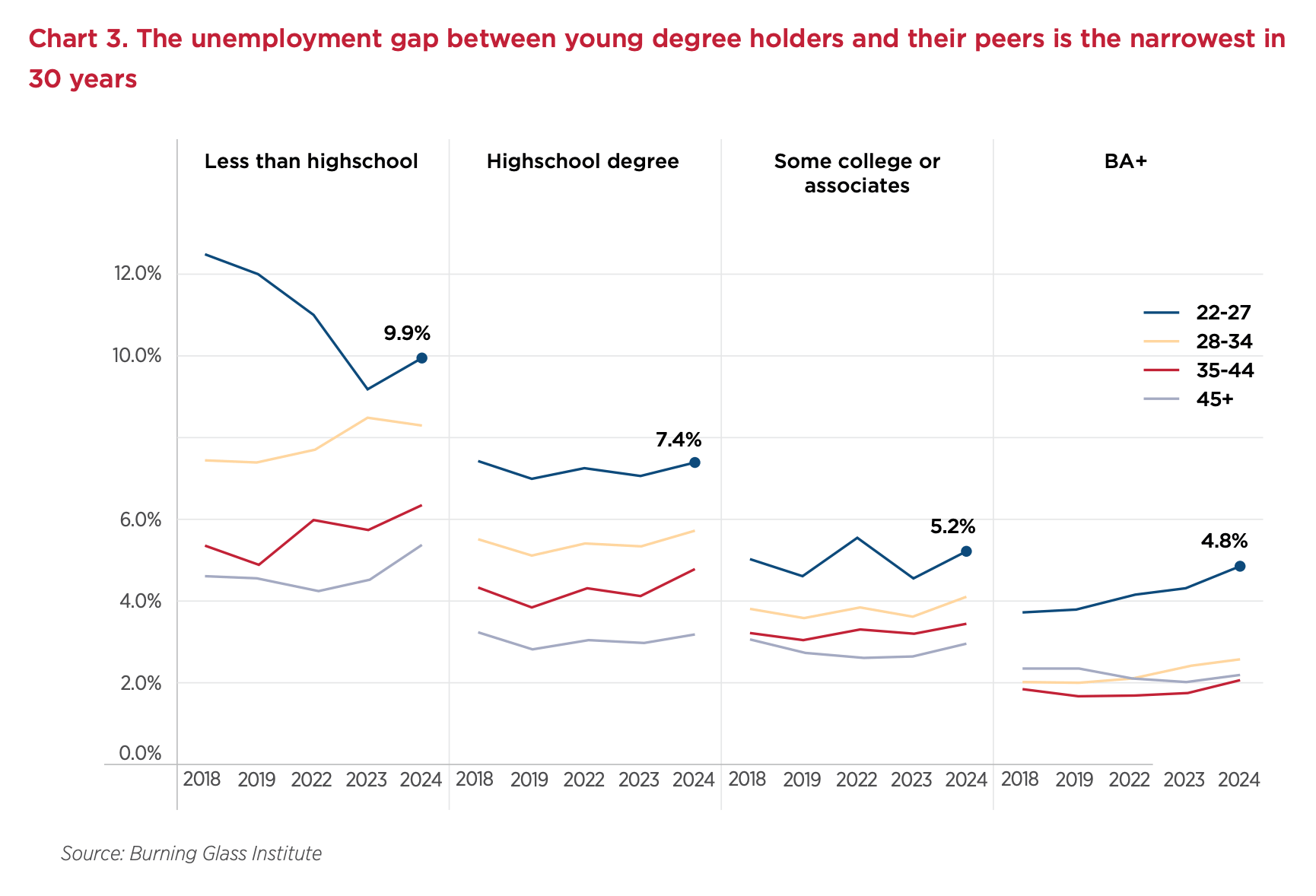

It is impossible to ignore just how tough the market has become for new graduates. As Burning Glass shows, the unemployment rate for new grads has risen at the same time the rate for many other groups has declined.

Looking at 20-24 year olds, the unemployment rate for those with at least a bachelor’s degree increased from 5.2% in 2018-19 to 6.2% in the two years through June 2025. By contrast, rates for individuals with less education have generally declined since 2016-2017. As a result, the unemployment rate for young college grads is now higher than for any other group except those with only a high school diploma.

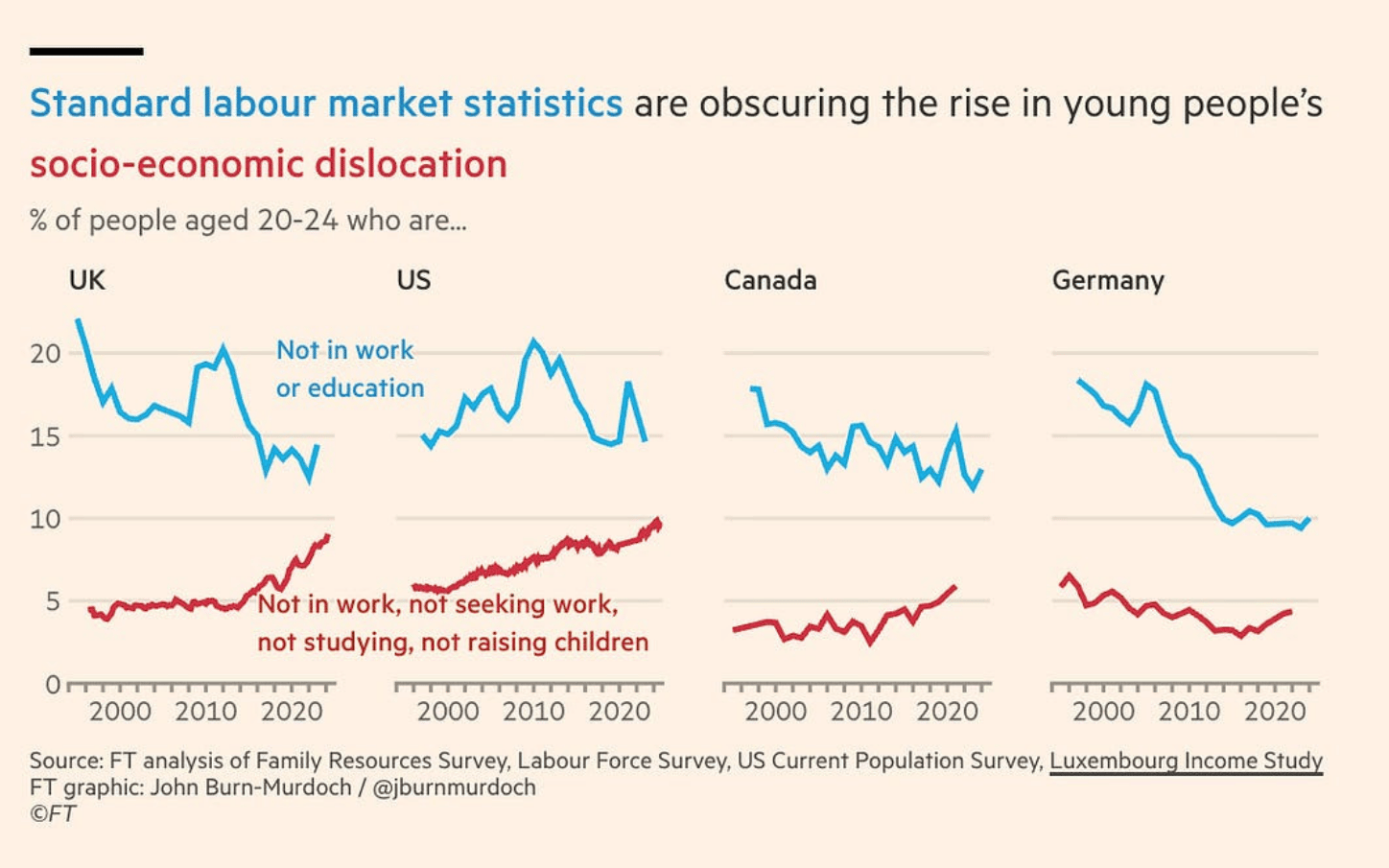

The falloff in hiring for those with bachelor’s degrees is true not only in the United States, where Burning Glass draws its data, but also internationally. Increasingly, young people are not only struggling to get jobs but are becoming disconnected from the labor market and not even seeking work.

According to early data from the National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE), the Class of 2025 has already submitted more job applications than the Class of 2024, yet is receiving fewer offers. More applications and fewer outcomes: that is what a tightening early-career market looks like on the ground.

Put simply, for many new graduates, the first step into the labor market has become much harder.

The argument: A structural shift in the job market

Several organizations are now making the case that the downturn in hiring for new graduates is driven by a deeper and more enduring restructuring of white-collar work, and that for this “expertise upheaval,” generative AI is reshaping the entry-level landscape by taking over precisely the kinds of tasks that used to give young graduates their start.

As Burning Glass puts it:

Artificial intelligence is eliminating entry-level positions where large language models can perform many of the junior tasks. The share of job postings requiring fewer than 3 years of experience has dipped in these occupations, while the relative demand for senior talent has grown

This shift, they argue, has fundamentally changed the shape of early-career work.

The disruption occurs because, in these roles, Generative AI excels at precisely the kind of foundational work that junior employees traditionally perform: research, first drafts, basic data analysis, and routine communications. As AI takes on these tasks, the traditional ‘stepping stones’ for junior employees erode. This creates a ‘Flipped Pyramid’ effect… drastically reducing the need for a large entry-level workforce.

Burning Glass is not alone in this view.

The Atlantic recently posed the question of what, exactly, is happening to new-graduate hiring, and one of the theories they highlighted echoed this argument about the changing structure of the workplace. They quote Harvard economist David Deming (emphasis mine).

The relatively weak labor market for college grads could be an early sign that artificial intelligence is starting to transform the economy… When you think from first principles about what generative AI can do, and what jobs it can replace, it’s the kind of things that young college grads have done

Other analysts are sounding the same note. Oxford Economics, for example, argues that “there are signs that entry-level positions are being displaced by artificial intelligence at higher rates.”

There does seem to be a significant change in early-career hiring, and it is one that needs attention. But the rush to attribute it to Gen AI (as opposed to seeing that as an accelerant of a pre-existing trend) across the board has some real problems.

The flawed and conflated argument

The emerging narrative from Burning Glass and others rests heavily on economic research that attempts to map which jobs, tasks, and early-career roles are “vulnerable” to AI. Their argument is built on frameworks such as Burning Glass’s Expertise Upheaval model, developed with Joseph Fuller and Michael Fenlon, that classify occupations by how easily generative AI could take over the foundational tasks typically performed by new graduates. Similar analyses, including work by Eloundou and Manning and studies from the Philadelphia Fed, argue that higher-paying, degree-requiring jobs are among the most exposed to AI substitution.

The problem is that much of this work is premature and speaks more to what could happen than to what is actually happening.

First, the research itself has substantial limitations. Many of these models start with a theoretical question, “What could AI potentially do?” and then leap to the conclusion that these tasks will be automated away. This makes the analyses inherently speculative. Actual research increasingly finds no evidence to support these claims. Sarah Eckhardt and Nathan Goldschlag of the Economic Innovation Group think tank found no detectable effect of AI on recent employment trends for most measures, and where there was an impact it was less than 1 percent. Economists Anders Humlum and Emilie Vestergaard reached similar conclusions, noting that there is still no measurable impact on employment or earnings in any occupation. Predictions about AI’s long-term labor-market disruptions remain just that: predictions.

Second, much of the underlying evidence is anecdotal. Even the Burning Glass report relies heavily on employer anecdotes rather than data. Anecdotes about managers avoiding Gen Z or relying more on senior hires do not constitute evidence of a structural, AI-driven labor shift.

Third, the analyses are logically forward-looking but practically static. They assume that:

demand for various roles stays constant

organizations adopt AI cleanly and uniformly

the presence of an AI-capable tool automatically shifts staffing models

In reality, workplace adoption of AI is messy, uneven, and highly path dependent. AI does not simply “slot in” to displace junior workers. It requires workflow redesign, management buy-in, data governance structures, training, and cost justification, none of which these studies seriously examine. While I believe it is likely that AI will change the nature of expertise, you cannot reliably predict how that will happen based on first principles.

Fourth, these models ignore the fact that many labor-market trends they attribute to AI predate AI’s widespread introduction. The Yale Budget Lab points out that although the occupational mix is evolving, the shifts are not unusually large and show no relationship to measures of AI exposure, automation, or augmentation. Similarly, a recent New York Fed survey found that firms report negligible effects of AI on hiring as of a year ago, well after the actual job market changes were well established.

Even Burning Glass’s own report shows a growing gap between young workers’ unemployment rates starting at least in the late 2010s, well before the widespread adoption of Gen AI (look at the rightmost part of the chart).

Taken together, these shortcomings suggest that while AI may eventually reshape early-career work, the evidence simply does not support the idea that it is the primary driver of today’s slump in new-graduate hiring. For now, the structural AI explanations reflect a compelling narrative, but not one backed by real labor-market data.

Not denying the potential future impacts

Yet even if they are wrong about what is happening right now, I still think they are on to something. It is not only that using AI to do some of the grunt work that new hires typically do makes logical sense. There are also signs that organizations are explicitly working on training AI to perform these roles. OpenAI is reportedly hiring former management consultants to train AI on the tasks done by junior associates, and other companies are hiring all kinds of experts to train AI in tasks that can be automated.

For all the reasons described above, I do not think this is happening yet, at least not at a sufficient scale to reshape the workforce. That being said, the hiring slump is real. Something is happening to cause the falloff in hiring of new graduates even while senior hiring remains strong. I think that higher education ideally needs to think about understanding the problem in two related but distinct phases.

The initial phase, where we currently find ourselves. Hiring of new graduates is down, but it is not yet due to entry-level jobs actually being replaced by AI.

A later phase, where AI (along with other changes) has shifted the nature of expertise and the way it is built in the workplace.

Parting thoughts about solutions

The problem is that the solutions being proposed right now are the usual grab bag of suggestions about improving career services or building stackable microcredentials, and they are so unspecified that they are unlikely to fix anything.

Even if we get more specific, there is a real danger that if we focus on the second phase (the expertise upheaval) rather than the first phase and the more immediate causes of the graduate hiring slump, we will fail to address the issue or address it only partially. I do not have a complete grasp of the causes of this first phase, and neither do most observers. But getting clear on those causes is absolutely critical if we want to devise strategies that will actually help.

We do need to better understand the expertise upheaval more fully and to prepare for how we might respond if and when it takes shape. But it is even more important that we evaluate the current challenges accurately and avoid addressing possibilities rather than realities.

The main On EdTech newsletter is free to share in part or in whole. All we ask is attribution.

Thanks for being a subscriber.