On Student Success: Give it a read

Some great content in this sister publication

Was this forwarded to you by a friend? Sign up, and get your own copy of the news that matters sent to your inbox every week. Sign up for the On EdTech newsletter. Interested in additional analysis? Upgrade to the On EdTech+ newsletter.

A few months ago, Morgan launched her own newsletter On Student Success (subscribe here), adding to her analysis in the On EdTech newsletter and going deeper on a topic of particular interest to her. Student success is a multi-faceted topic, tying in the focus on data rather than action, the framing of durable skills, the faculty role in transfer decisions, liberal arts graduate earnings, and what happens when students are unable to enroll in the courses they need.

In examining these varied aspects of college and university life, Morgan shows that while awareness of student success challenges is widespread, the deeper problems lie in institutional systems, and in the tendency to view student success through too narrow a lens.

Her posts over the past six months ask not just whether higher education cares about student success — most institutions clearly do — but whether we are willing to deal with the challenging decisions necessary to improve how our students succeed, or not.

I have included a sample of posts below to give you a sense of the On Student Success newsletter. I am obviously biased, but I love reading her posts and learning from her insights. Give these a read and subscribe if you’re interested.

In this post, Morgan takes aim at a pervasive pattern in higher education’s approach to student success: institutions identify a problem, purchase a tool (an early alert system, CRM, dashboard, etc.), implement it, and then stop. The missing link is not insight but follow-through.

She outlines several hypotheses for why this happens, but they largely converge on a common theme: institutions treat data collection and system implementation as the end goal rather than as the beginning of the work. As Morgan puts it, data must be “the start of the journey, not the finish.”

In this post, Morgan uses an analysis by Burning Glass economists to highlight some of the problems associated with using short-term post-graduation earnings as proxies for institutional value. The Labor Matters post focuses specifically on selective liberal arts colleges (SLACs). Graduates of these institutions tend to earn less immediately after graduation than graduates of other elite institutions, though many catch up later in their careers.

However, one of the examples the post uses, Bryn Mawr College, illustrates the difficulty of accounting for the broader forces that shape earnings, including gender discrimination and regional pay variation. The data show Bryn Mawr graduates starting at salaries well below their peers. The authors argue that they have controlled for gender, but how do you control for gender at an institution that (according to IPEDS and common knowledge) enrolls an exclusively female student body?

This is not merely a methodological oversight. It highlights the deeper problem of relying on accountability metrics that ignore structural forces and risk penalizing institutions for societal inequities beyond their control. As Morgan argues, “Punishing institutions for the latter is deeply problematic and ultimately harmful to society.”

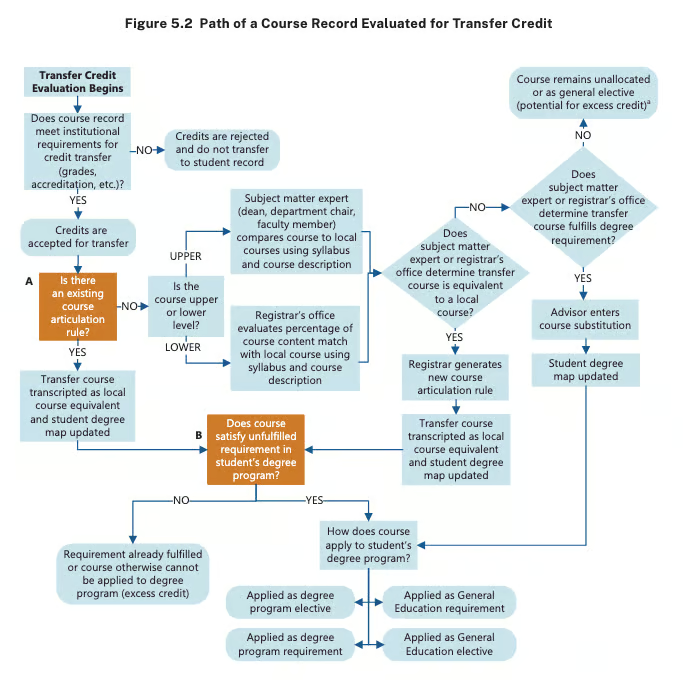

Facilitating student transfer between institutions is a critical challenge for many colleges and universities. In this post, Morgan highlights new MDRC research to show that while transfer is often framed as a technical or advising problem (messy data, too few advisors, confusing requirements), many transfer barriers are in fact cultural and structural. She underscores how the MDRC study reveals a breakdown in the transfer “two-step”: credits may be accepted by the receiving institution but never actually applied toward a major. This disconnect significantly delays student progress and increases time and cost to degree.

These breakdowns often stem from the faculty role in evaluating transfer credits. Factors such as skepticism about the quality of instruction at community colleges, minor catalog description mismatches, and unrealistic or burdensome documentation requests can lead to lengthy review processes in which credits ultimately do not count toward a course of study.

As Morgan argues, the issues highlighted in the MDRC study are critical because most “best practices” overlook faculty discretion and the documentation burden. Until institutions address how faculty roles, standards, and evidence requirements operate within the transfer process, meaningful improvement is unlikely.

Most “best practices” overlook faculty discretion and the documentation burden. Until institutions address how faculty roles, standards, and evidence requirements operate within the transfer process, meaningful improvement is unlikely.

Current conversations about student success and higher education accountability inevitably include some discussion of soft or durable skills. In this post, Morgan takes aim at the concept, arguing that much of this coverage is frustrating because it omits the most important meta-skill: learning how to learn. She also critiques the tendency to frame durable skills as relevant only to the workforce, rather than as essential for success during college itself.

Morgan argues that we need to conceptualize durable skills around the capacity to learn — and to recognize them as critical to student success while students are still enrolled, not merely after they graduate.

In this post, Morgan synthesizes two innovative research streams (one on community college waitlists in California and another on a unique exercise in allocating course places at Purdue based on an algorithm) to overturn the old assumption that course shutouts don’t matter. While overall four-year graduation rates may not shift dramatically, shutouts increase stop-out risk, reduce likelihood of ever completing the course or subject, affect major choice and produce gender-differentiated labor market impacts. Morgan uses these important studies to show that in order fully to understand student success, we need to look at issues such as being shut out of courses.

But for me, the most important takeaway from this research is the value of taking a wide-angle view when measuring impact. Rather than fixating on a single outcome, such as on-time graduation, both research teams show how being shut out of a course can make the student journey more difficult and less rewarding. If we’re serious about improving student success, we have to examine the full experience, not just the finish line.

The main On EdTech newsletter is free to share in part or in whole. All we ask is attribution.

Thanks for being a subscriber.