Three Competing Ways States Are Defining the “Value” of Higher Education

Three states aren't even waiting for the new OBBB rules to go into effect

Was this forwarded to you by a friend? Sign up, and get your own copy of the news that matters sent to your inbox every week. Sign up for the On EdTech newsletter. Interested in additional analysis? Upgrade to the On EdTech+ newsletter.

Accountability has finally arrived as a front-burner issue in higher education policy. The One Big Beautiful Bill (OBBB) accountability framework has drawn understandable attention as federal rules move toward finalization. But what’s striking, and easy to miss, is that state policy is already moving, even before the federal ink is dry.

In recent weeks, multiple states have advanced legislation tying state funding, program approval, or institutional liability directly to federal accountability concepts.

Late last week, Indiana’s state senate just passed a bill to cut off state funding for “low-earning programs” based on the OBBB definitions.

One week earlier, a bill was introduced in Nebraska to the same effect.

On the same day (January 21st), a bill was introduced in New Hampshire, also seeking to cut off state aid to “low-earning programs.”

All of this happening even though the US Department of Education (ED) won’t have the new rules completed until July.

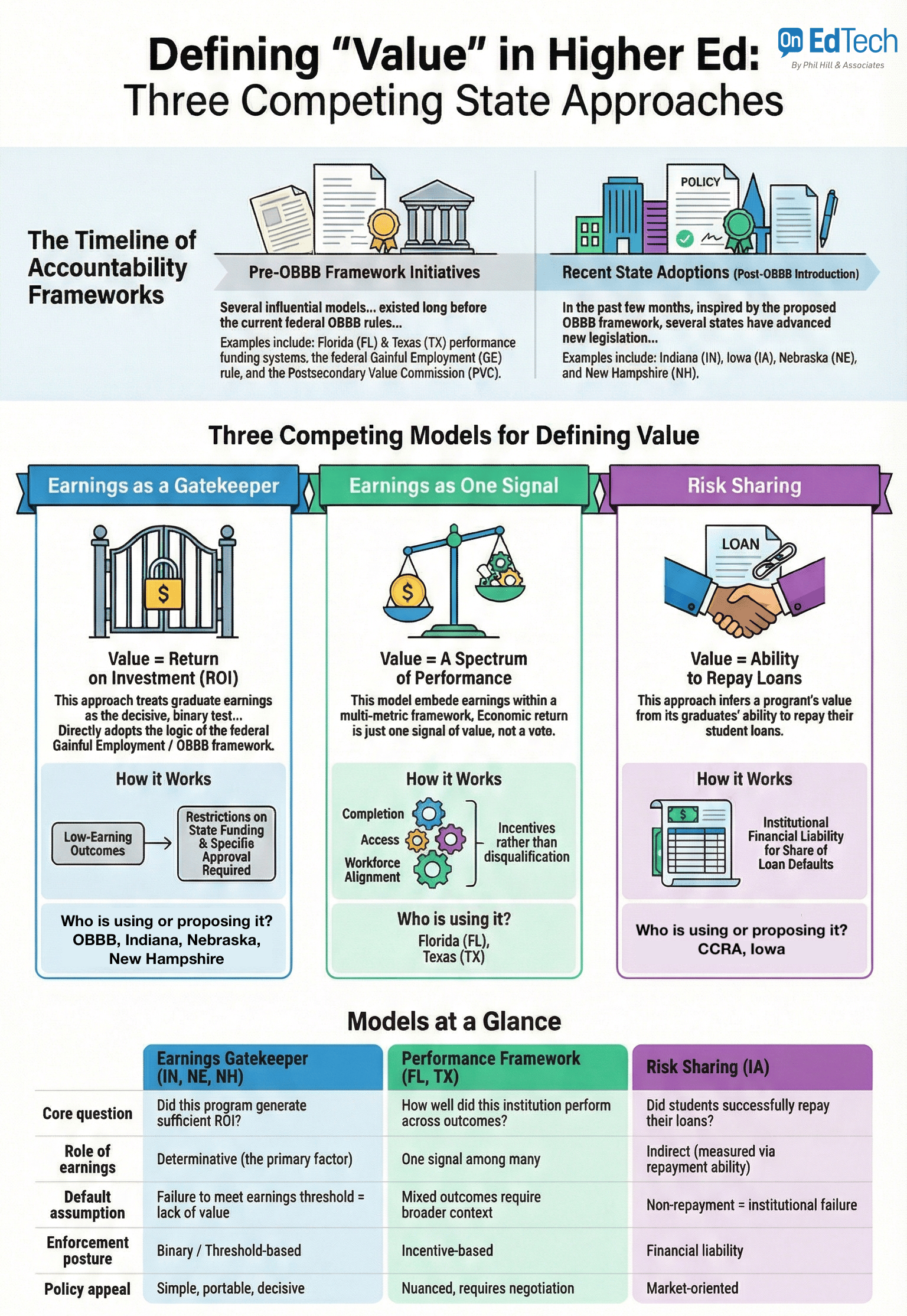

Stepping back from individual bills reveals a deeper and more consequential pattern. States aren’t just debating whether to hold higher education accountable. They are adopting very different answers to a more fundamental question:

What determines the value of higher education?

Right now, three distinct, and increasingly competing, approaches are emerging. Which one gains momentum will shape higher education far more than the details of any single rule.

1. Earnings as a gatekeeper: value equals ROI

The first approach treats return on investment as the decisive test of value. This is the logic embedded in the federal Gainful Employment / OBBB framework and now being debated in states such as Indiana, Nebraska, and New Hampshire.

Under this model, earnings are not merely informative. They are determinative. If a program fails an earnings test—typically defined as falling below a national high-school benchmark—it is presumed to lack sufficient value unless the institution can justify an exception.

Proposed state statutes increasingly echo this posture with language referencing:

“Low-earning outcome programs” as defined in federal law

Mandatory approval requests to continue affected programs

Restrictions on state funding tied directly to earnings outcomes

The appeal is obvious. This approach is simple, portable, and bipartisan. States don’t need to invent metrics or build new data systems; rather, they can simply import federal definitions and thresholds.

But that simplicity rests on a strong assumption: that earnings premium is the primary determinant of educational value. Other considerations such as regional labor markets, institutional mission, or public-service roles may be acknowledged rhetorically, but they do not override the metric.

I’ve written before about the flaws of this blunt-instrument approach, especially its tendency to penalize regionally focused institutions and workforce programs serving lower-wage labor markets. Since the benchmarks tend to be state-level medians, programs located in lower-income areas have to increase earnings much more than for programs in higher-income areas to pass the test.

What’s new is not the metric, but how quickly states are beginning to jump on the bandwagon.

2. Earnings as one signal among many: value as performance

A second approach, exemplified by Florida and Texas, the latter for the community college system, reflects a very different philosophy, even though graduate earnings still matter. Other examples that include some level of graduate earnings include Tennessee, Ohio, and Washington.

In these systems, earnings are embedded within multi-metric performance frameworks. They help shape funding allocations or institutional comparisons, alongside measures such as completion, access, workforce alignment, and improvement over time.

Statutory and regulatory language emphasizes:

Performance metrics and weighted outcomes

Relative institutional performance

Incentives rather than disqualification

Here, return on investment (ROI) is a signal, not a veto. Programs and institutions are not deemed valueless because of one outcome. Instead, earnings contribute to a broader picture of performance.

This approach treats value as multi-dimensional. Economic return matters, but it does not settle the question on its own.

It’s also harder to build. Performance-based funding systems require negotiation, institutional buy-in, and sustained political commitment. Which helps explain why, despite their sophistication, they are not the path of least resistance.

3. Risk sharing: value inferred from repayment failure

A third approach is being considered in Iowa and somewhat mirrors earlier House Republican proposals under the College Cost Reduction Act (CCRA).

Rather than focusing on earnings benchmarks, this model defines value through student loan repayment outcomes. Institutions would be financially liable for a share of student loan defaults, effectively sharing downside risk when students cannot repay.

The core logic is different but related:

If students can’t repay, the program failed to deliver sufficient economic value

Institutions should internalize some of that failure

This approach avoids explicit earnings comparisons, but it still embeds a strong economic assumption: repayment success is the ultimate test of value, regardless of other benefits.

It’s not just statutes: non-legal signals point in the same direction

What makes this moment especially important is that the shift isn’t confined to legislation.

State systems and commissions are also shaping how value is discussed and normalized. For example, the University of North Carolina System recently released an ROI study estimating a $500,000 median lifetime return for its graduates. That’s not regulation, but it sends a clear signal to policymakers and the public that earnings-based analysis is a legitimate way to talk about higher education’s worth.

Similarly, efforts like the Postsecondary Value Commission are advancing frameworks that place earnings, repayment, and labor-market alignment at the center of value discussions. These initiatives matter because they help define what metrics feel credible and reasonable long before they appear in law.

Together, these non-legal moves reinforce the same trend: economic return is becoming the dominant language of value, even when it’s not yet the dominant enforcement mechanism.

Emerging Model Comparison

Stepping back, the differences become clearer when you line them up1 .

Why the OBBB approach may be gaining momentum

These three approaches are not easily compatible. You can’t simultaneously treat earnings as a hard eligibility gate, a contextual performance signal, and a back-end risk-sharing trigger without creating conflicting incentives.

Yet the earnings-gatekeeper model appears to be gaining momentum for a simple reason: it’s the path of least resistance.

Federal definitions already exist. The politics are straightforward. The enforcement is clean. States can act quickly without building new frameworks or reopening value debates from scratch.

Ease of adoption, however, is not the same as quality of design. And we’ll have to see if any of the new bills succeed and become statute.

Implications

Looking beyond the details, it appears that we are entering a period of competition over how value itself is defined.

If the earnings-premium model becomes the default—not because it’s best, but because it’s easiest—institutions will increasingly be judged through a single economic lens, even as leaders continue to talk about access, mission, and regional impact.

This is a moment to pay attention to trajectory, not just detail. The rules are still evolving, but the direction of travel is becoming clearer.

Stay tuned.

The main On EdTech newsletter is free to share in part or in whole. All we ask is attribution.

Thanks for being a subscriber.

1 Edited based on NotebookLM initial creation; alt text from Access Hounds.